MAKING ART is difficult. Doing it when you’re struggling with an illness you know is going to kill you is a higher level of achievement. “How do I embrace this thing and make it OK, or make myself able to live with it and produce and go on from there? How do I live every day with despair?” wrote painter Hugh Auchincloss Steers after he was diagnosed with HIV at age 25. The answer was: by constantly painting canvases depicting men who are ill, men in partial or complete undress, ambiguously intimate in their private spaces. Steers did this for the remaining seven years of his life, almost up to the day he died: March 1, 1995.

The raw force and beauty of Steers’ figurative painting is on display in a solo exhibition of work not shown previously, at Alexander Gray Associates through July 27th. The Chelsea gallery, which represents the artist’s estate, last exhibited Steers’ work in 2015. In fall 2017, two of the artist’s works were included in AIDS at Home: Art and Everyday Activism, an exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York. In 2015, Visual AIDS, a New York-based organization dedicated to HIV/AIDS awareness through visual art projects, published Hugh Steers: The Complete Paintings, 1983–1994, a comprehensive look at Steers’ work with accompanying essays, including author Cynthia Carr’s profile of the artist.

Carr discusses Steers’ artistic influences as well as the complexity of his personal history and the troubled relationships he had with his family despite his glamorous WASP pedigree. As a gay man at Hotchkiss, an exclusive boarding school in Connecticut, Steers felt alienated. The friendships he made there were mostly with women who also felt as though they were on the outside looking in. One new classmate came to Hotchkiss from a school in Madrid. On her first day, she followed the custom of not bringing books into the dining room. Seeing this, Steers went over to her and said, “You dropped your books with such panache. I have to meet you.” Carr reports they became best friends.

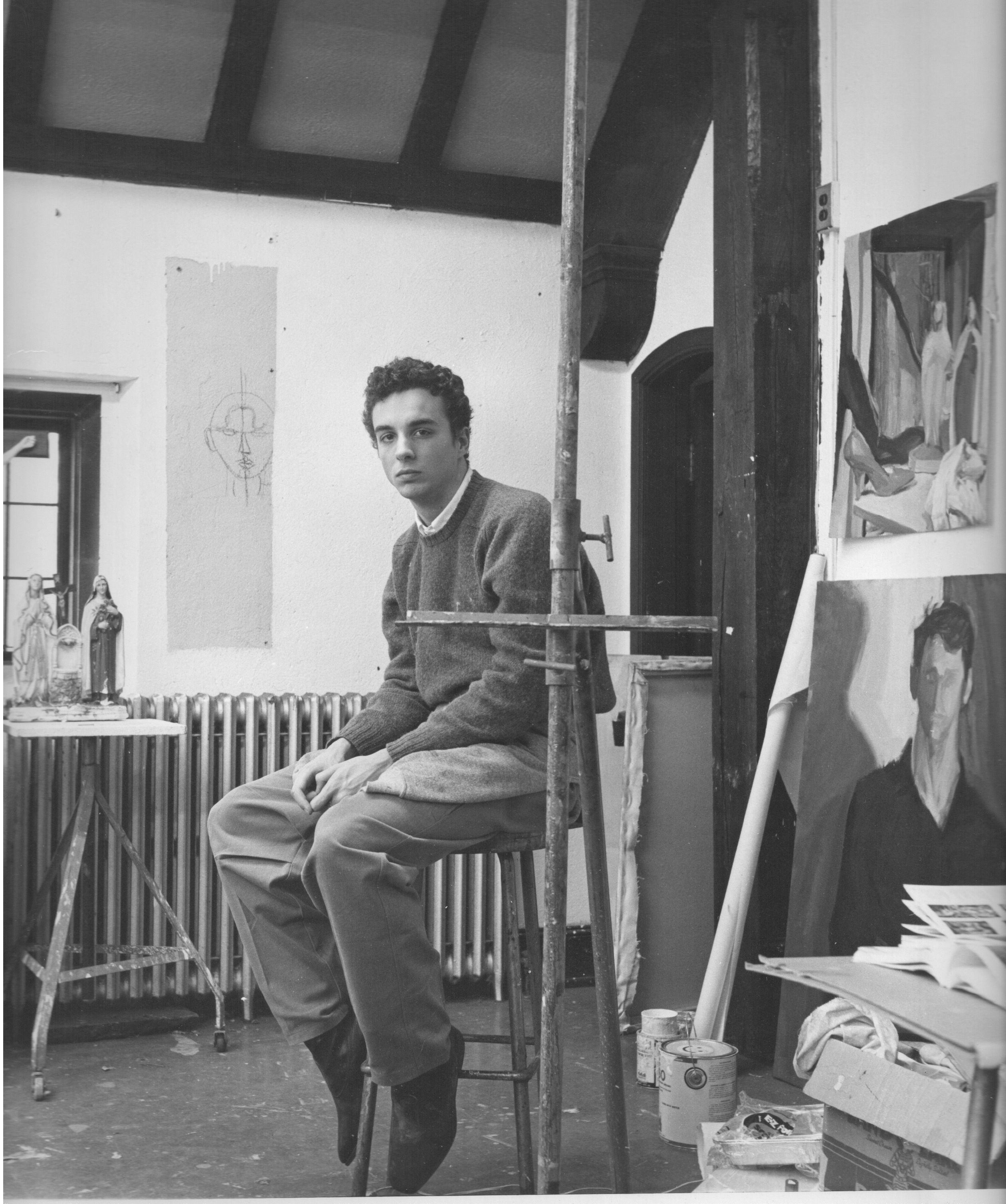

Born in Washington, D.C., to Nina Gore Auchincloss and Newton Steers, a mutual funds entrepreneur and later a U.S. Congressman from Maryland, Steers grew up in the affluent suburban enclave of Bethesda, Maryland. He was a graduate of Hotchkiss and Yale, the grandson of financier Hugh D. Auchincloss, who owned Hammersmith Farm in Newport and who was also the stepfather of Jackie Kennedy (Steers and JFK Jr. played together in Newport in the summer), a descendant of statesman Aaron Burr, and the nephew of American author Gore Vidal. In ways similar to Vidal, he considered all of this to be a very mixed blessing. He sought to make his way as a painter largely independently of his social connections. This extended to numerous periods in his short artistic career as he struggled to pay the rent on his rundown apartments that doubled as studios.

At first glance, a Steers painting is a tipoff that all is not right in the world. AIDS is often lurking, but to suggest that his paintings are solely about his own illness—a death sentence for thousands of mostly gay and bisexual men in this period—is to miss their broader significance. At the same time seeing them strictly through a political lens is equally reductive. If anything, as figurative paintings, they were anomalous if not retrograde at a time—the 1980s and ’90s—when the fashion was more toward conceptual and performance art, or photography, as illustrated by the popularity of Robert Mapplethorpe. Steers was attuned to the art that was in vogue, but he was doggedly committed to representational art and to depicting the male figure in a centuries-old tradition of the great masters, such as Caravaggio, Velázquez, and Goya (whose influence is evident in his work), and of more recent artists like Edward Hopper and David Park. In a 1992 interview, Steers commented on the mood in his paintings: “I think I’m in the tradition of a certain kind of American artist—artists whose work embodies a certain gorgeous bleakness.”

One of the bitter ironies of the AIDS epidemic is that it began at the end of the very decade, the 1970s, when gay men had created a community for the first time, and on a large scale. Gay liberation, though its roots ran farther back, essentially came out of the radical politics and cultural usurpations of the previous decade. It flowered with Stonewall and in the fervor of gay pride celebrations on Castro Street, in the Village, and in other large urban centers. Gay publications such as The Bladein Washington, The Advocate, which originated in Los Angeles, and San Francisco’s Gay Sunshineemerged to meet the interests of a growing audience. A new, openly gay literature arose with books by young writers, such as Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Danceand Edmund White’s Nocturnes for the King of Naples.

Tribalism had been an element of hippie sit-ins and be-ins and other gatherings in the ’60s. Parks were filled with young men and women dancing to guitars and drums, the air thick with incense and marijuana smoke. A little later, hordes of shirtless gay and bisexual men would lose themselves in the crowd at all-night discos or flock to the beaches at Fire Island for entire weekends. Steers’ work, with its allegorical references—some of the figures wear paper bags over their heads; black cats and crows enter these spaces—is a reminder of how drastically things would change. AIDS was sending men back into isolation and darkness. The tribe was splintering. Does so-and-so have “it”? Could I catch it from him? These were questions that people, both gay and straight, were asking themselves in the early years of the epidemic.

The mood in Steers’ paintings, which usually involve two men in relation to one another, is antithetical to the crowd euphoria of the pre-AIDS period. A Steers painting isn’t about “us”; it’s more about “you and I.” Nor is it about the anonymity of the baths or the music- and drug-induced highs of the bars. These men are fenced in, their lives intersect; they are consigned to one another. They are lovers, or have been; or per- haps they were acquaintances brought together because, as a result of being sick, they were going broke. In many cases they appear to be dying. They inhabit a multi-layered emotional zone very different from that of the packed dance floors or the sun-drenched beaches of a few years before.

The paintings draw the viewer into a private space: a bare room with a bed, or a bathroom with a tub, sometimes the old-fashioned clawfoot style, a symbol of luxury in the Victorian era. In many American cities you can still find them: in gritty, unrenovated apartment buildings, like the ones Steers lived and worked in, tubs left over from the early 20th century when the buildings were constructed. In Steers’ paintings, the “claws” can seem animated and menacing.

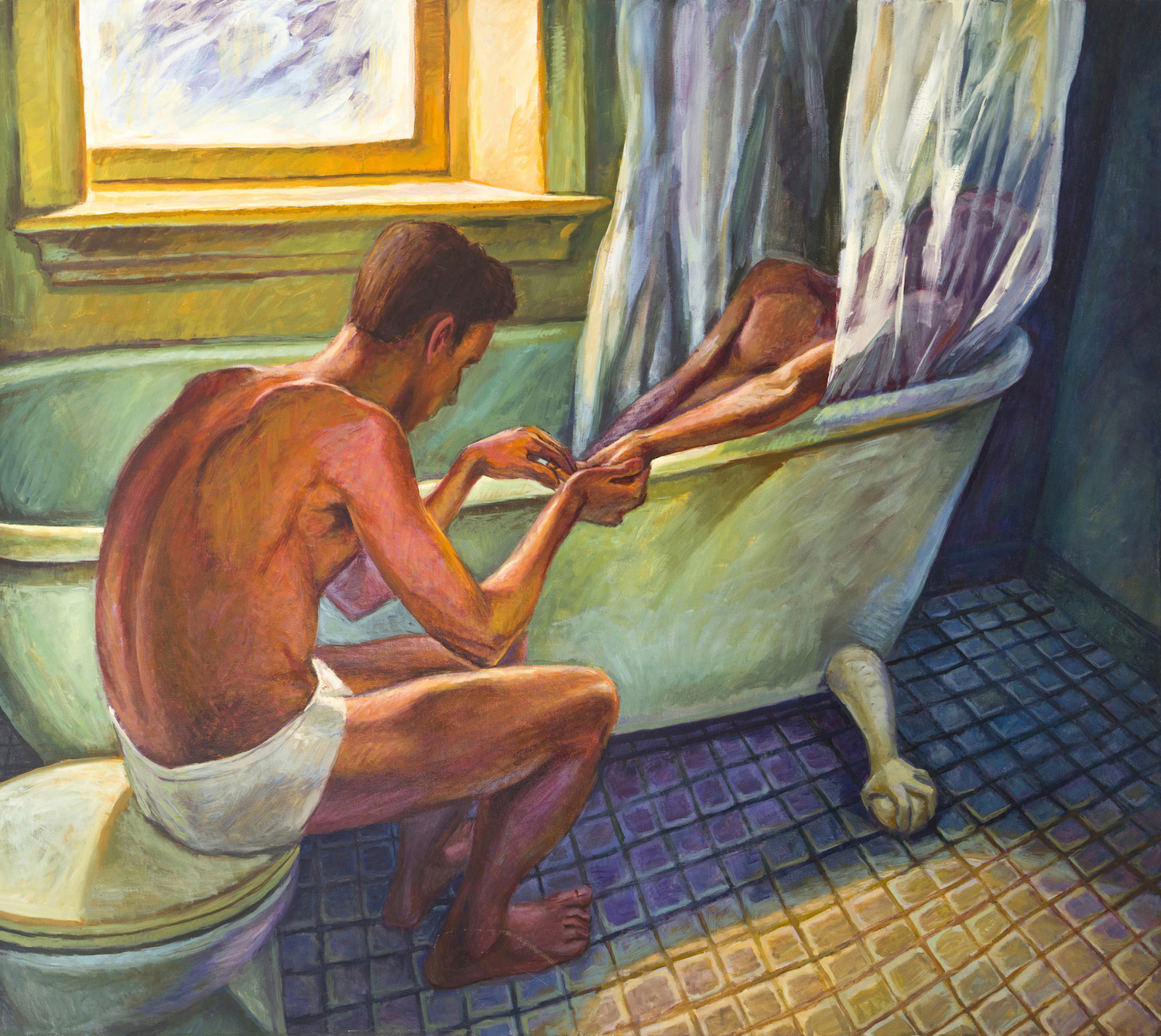

In Bath Curtain(1992), for example, a man in white underwear sits on a toilet, his back arched toward the bathtub. His wrists are thin in contrast to his thick, muscular torso. He is holding the hand of the man who lies in the bath, his face shrouded by a white shower curtain, his arms and one shoulder visible. The large (64- by 72-inch) painting’s composition divides the space diagonally so that the figure of the seated man pushes left into the viewer’s space, echoing Pierre Bonnard’s many great “bath” paintings that divide or flatten the plane, such as Large Nude in the Bathtubfrom 1924. But while Bonnard’s figures often have a kind of muted emotionality, Bath Curtainis infused with a tenderness wrung out of suffering. The love between the seemingly healthier seated man and the leaner one bathing is palpable.

The influence of Bonnard can also be seen in Steers’ color palette, in the intermixing and soft suffusion of pale yellow, green, and violet tones on the windowsill, tub, and tiled floor. Yet there is a key difference. Bonnard’s female figures blend in with the walls and the other objects in the picture, as seen in Large Nude, while in Steers’ Bath Curtain, the harsh, hot, orange-red and brown flesh tones of the bent figure’s back are in opposition to the low-key colors of the surroundings. George Bellows’ boxing pictures come to mind, and also the use of a vibrant red for skin tones by Marsden Hartley, as in his Christ Held by Half-Naked Men(1940–41), a painting that also has a strong thematic connection to Steers’ Bath Curtain.

Steers said this about his work: “A lot of my art has to do with that primal idea of drawing a painting of the hunt on the side of the cave. … It’s like a conjuring. I would like to be able to act or have someone care about me the way some of the people in my paintings act or care about each other. It’s as if painting it will make it become real.”

Although the figures in his paintings are sick and vulnerable, they are imbued with a physicality, an erotic fire. AIDS is ruining their bodies and impairing their mental faculties, yet despite this loss of power, there is defiance, affirmation—even a sexual affirmation. You can see it in numerous paintings in which a figure is wearing high heels. Steers had an interest in drag from a young age and used it symbolically as an antidote to defeat. An earlier oil on cardboard, Title unknown(ca. 1985), shows two pairs of bright red stilettos side by side. In one, a ripe pear appears in the foreground; in the other, the heel point of one of the shoes is stuck in a jar of Vaseline. Steers wrote: “Shoes like that are an amazing thing. They are so structured and there’s an architectural quality to them. They’re culture run wild, and yet they’re linked to a very sexual quality.”

Even in the late 1980s, the trappings of transvestism were not always met with open arms, whether in the gay world or the straight world. In 1994, the year before Steers died, he commented to art critic Holland Cotter that the commercial gallery that had been showing his work in the ’80s was finding his more recent “I’m-gonna-wear-heels-and-fuck-you” attitude less acceptable. Steers subsequently began exhibiting with maverick gallerist Richard Anderson, who risked showing up-and-coming artists and was more receptive to the way that Steers’ no-holds-barred work was evolving.

In Man and IV(1994), another large (65- by 47-inch) canvas, a tall, thin man wearing a white hospital gown that comes up well above his knees stands in white stilettos, hands on his hips, an IV attached to his forearm. He stares down the viewer in such a way as to say something like, “Yeah, I’m sick, and it sucks. But I’m not done.” Gender studies professor James Smalls, in one of the essays in the Visual AIDS monograph on his œuvre, mentions that Steers saw the figure in this painting, part of the artist’s “Hospital Man” series, as “a superhero fighting for the sexual rights of the sick.”

At the end of his life, despite many friendships with both sexes, and having had intimacies with men who might be described as lovers, Steers regretted that he had never had a “romantic” relationship. He was also quoted as saying that he never felt at home in the world, so it wasn’t that hard to leave. As a possible explanation, Carr mentions a line from Uncle Gore’s Palimpsest: “None of us brought up in a world of such crude publicness tends to trust much of anyone, while those who mean to prevail soon learn the art of distancing the self from dangerous involvements.”

What Steers did trust was painting. “There’s nothing like an exceptionally good passage of paint to make me feel good,” he said. When he died, his ashes were divided, with some scattered at Newport, another portion in Narragansett Bay. The remaining ashes were placed, along with his brushes and paints, inside his painter’s box, which was buried in the Auchincloss plot at the cemetery.

James Cassell is a painter and visual arts writer who lives in Silver Spring, MD. He last wrote about artist Martin Wong in these pages. Visit his website at www.jamescassellart.com.